Jesus Said That He Laid Down His Life Is That He Would Pick It Up Again King James Bible Gateway

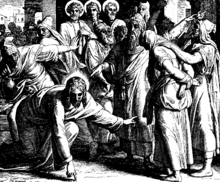

Christ and the woman taken in adultery, drawing by Rembrandt

Jesus and the woman taken in adultery (or the Pericope Adulterae [a]) is a passage (pericope) establish in John 7:53-viii:i–eleven, that has been the subject of much scholarly discussion.

In the passage, Jesus was teaching in the Second Temple after coming from the Mountain of Olives. A group of scribes and Pharisees confronts Jesus, interrupting his teaching. They bring in a woman, accusing her of committing adultery, claiming she was defenseless in the very act. They tell Jesus that the punishment for someone like her should be stoning, every bit prescribed by Mosaic Constabulary.[1] Jesus begins to write something on the footing using his finger. Merely when the woman's accusers keep their challenge, he states that the one who is without sin is the ane who should bandage the first rock at her. The accusers and congregants depart, realizing not ane of them is without sin either, leaving Jesus alone with the woman. Jesus asks the woman if anyone has condemned her and she answers no. Jesus says that he, likewise, does not condemn her, and tells her to get and sin no more.

There is now a wide academic consensus that the passage is a later interpolation added later on the earliest known manuscripts of the Gospel according to John. Although it is included in all modernistic translations it is typically noted as a after interpolation, every bit it is by Novum Testamentum Graece NA28. This has been the view of "most NT scholars, including most evangelical NT scholars, for well over a century" (written in 2009).[2] The passage appears to have been included in some texts by the 4th century, and became generally accepted by the 5th century.

The passage [edit]

John 7:53–eight:11 in the New Revised Standard Version:

53 And then each of them went home, 1 while Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. 2Early in the morning he came again to the temple. All the people came to him and he sat down and began to teach them. iiiThe scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery; and making her stand up before all of them, 4they said to him, "Instructor, this woman was caught in the very act of committing infidelity. 5Now in the law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what exercise y'all say?" 6They said this to examination him, and then that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. 7When they kept on questioning him, he straightened upward and said to them, "Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." eightAnd one time again he bent downwardly and wrote on the ground. 9When they heard it, they went away, one by ane, kickoff with the elders; and Jesus was left alone with the woman continuing before him. 10Jesus straightened up and said to her, "Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?" 11She said, "No one, sir." And Jesus said, "Neither practice I condemn y'all. Get your way, and from at present on do non sin over again."

Manuscripts [edit]

The bulk of Greek manuscripts include the pericope or function of it, and some of these included marginal markings suggesting the passage is in doubt. Codex Vaticanus, which is paleographically dated to the early 300s, does contain a marking at the end of John chapter 7 with an "umlaut" in the margin alongside a distinctive bare infinite following the finish of the Gospel of John, which would convey that the manuscript copyist was aware of additional text post-obit the end of John 21 – which is where the pericope adulterae is plant in the f-ane group of manuscripts.

The Latin Vulgate Gospel of John, produced by Jerome in 383, was based on the Greek manuscripts which Jerome considered aboriginal exemplars at that time and which contained the passage. Jerome reports that the pericope adulterae was establish in its usual place in "many Greek and Latin manuscripts" in Rome and the Latin Westward. This is likewise confirmed by other Latin Fathers of the 300s and 400s, including both Ambrose of Milan, and Augustine.

Leo the Groovy (bishop of Rome, or Pope, from 440 to 461), cited the passage in his 62nd Sermon, mentioning that Jesus said "to the adulteress who was brought to him, 'Neither will I condemn you; get and sin no more.'" In the early 400s, Augustine of Hippo used the passage extensively, and from his writings, it is also clear that his contemporary Faustus of Mileve as well used it.[ citation needed ] Augustine claimed that the passage was specifically targeted and improperly excluded from some manuscripts:

"Certain persons of little organized religion, or rather enemies of the truthful faith, fearing, I suppose, lest their wives should be given impunity in sinning, removed from their manuscripts the Lord's act of forgiveness toward the adulteress, equally if he who had said, Sin no more, had granted permission to sin."[3]

The pericope does not occur in the Greek Gospel manuscripts from Arab republic of egypt. The Pericope Adulterae is non in 66 or in 75, both of which have been assigned to the late 100s or early 200s, nor in 2 important manuscripts produced in the early or mid 300s, Sinaiticus and Vaticanus. The commencement surviving Greek manuscript to contain the pericope is the Latin-Greek diglot Codex Bezae, produced in the 400s or 500s (simply displaying a class of text which has affinities with "Western" readings used in the 100s and 200s). Codex Bezae is likewise the primeval surviving Latin manuscript to contain it. Out of 23 Erstwhile Latin manuscripts of John 7–8, seventeen contain at least part of the pericope, and represent at least three transmission-streams in which it was included.

Many modern textual critics have speculated that it was "certainly non role of the original text of St. John'due south Gospel."[4] The Jerusalem Bible claims "the author of this passage is not John".[v] Some have also claimed that no Greek Church Father had taken note of the passage earlier the 1100s.

However, in 1941 a large collection of the Greek writings of Didymus the Blind (313–398 AD) was discovered in Egypt, in which Didymus states that "We find in certain gospels" an episode in which a adult female was accused of a sin, and was about to be stoned, but Jesus intervened "and said to those who were near to bandage stones, 'He who has not sinned, let him take a stone and throw information technology. If anyone is witting in himself not to have sinned, let him take a stone and smite her.' And no one dared," and so along.[ citation needed ] As Didymus was referring to the Gospels typically used in the churches in his time, this reference appears to institute that the passage was accepted every bit authentic and commonly present in many Greek manuscripts known in Alexandria and elsewhere from the 300s onwards.

The subject of Jesus' writing on the ground was fairly mutual in fine art, especially from the Renaissance onwards, with examples past artists including those a painting by Pieter Bruegel and a cartoon by Rembrandt. In that location was a medieval tradition, originating in a comment attributed to Ambrose, that the words written were terra terram accusat ("earth accuses earth"; a reference to the cease of verse Genesis three:nineteen: "for dust you are and to dust yous will render"),[6] which is shown in some depictions in art, for case, the Codex Egberti. This is very probably a matter of guesswork based on Jeremiah 17:thirteen. There have been other theories about what Jesus would accept written.

Estimation [edit]

This episode, and its message of mercy and forgiveness balanced with a call to holy living, take endured in Christian thought. Both "let him who is without sin, cast the first stone"[7] and "become, and sin no more"[viii] take found their fashion into common usage. The English idiomatic phrase to "cast the first stone" is derived from this passage.[nine]

The passage has been taken as confirmation of Jesus' ability to write, otherwise simply suggested by implication in the Gospels, only the word "ἔγραφεν" in John 8:8 could mean "describe" besides as "write".[ten]

Mosaic Law [edit]

Deuteronomy 22:22–25 states:

If a man be found lying with a adult female married to an husband, then they shall both of them die, both the man that lay with the woman, and the woman: and then shalt thou put away evil from Israel.

If a dryad that is a virgin exist betrothed unto an husband, and a man notice her in the urban center, and lie with her; Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of that city, and ye shall stone them with stones that they die; the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the homo, because he hath humbled his neighbour's wife: so chiliad shalt put abroad evil from among you.

But if a man notice a betrothed dryad in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man merely that lay with her shall die: But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of decease: for as when a man riseth confronting his neighbour, and slayeth him, even so is this matter: For he constitute her in the field, and the betrothed dryad cried, and there was none to save her.

In this passage and also in Leviticus 20:10, "expiry is fixed as the penalty of adultery", applicable to both the homo and the woman concerned. Nevertheless, "stoning as the form of decease is only specified when a matrimonial virgin is violated".[11]

Textual history [edit]

John seven:52–8:12 in Codex Vaticanus (c. 350 AD): lines ane&2 end 7:52; lines iii&four start 8:12

According to Eusebius of Caesarea (in his Ecclesiastical History, composed in the early 300s), Papias (circa AD 110) refers to a story of Jesus and a woman "defendant of many sins" every bit being found in the Gospel of the Hebrews, which might refer to this passage or to one like it. In the Syriac Didascalia Apostolorum, composed in the mid-200s, the author, in the course of instructing bishops to exercise a measure of charity, states that a bishop who does not receive a repentant person would be doing wrong – "for you do not obey our Savior and our God, to do as He too did with her that had sinned, whom the elders fix before Him, and leaving the judgment in His easily, departed. But He, the searcher of hearts, asked her and said to her, 'Have the elders condemned thee, my daughter?' She said to Him, 'No, Lord.' And He said unto her, 'Get your way; neither do I condemn thee.' In Him therefore, our Savior and King and God, be your pattern, O bishops."

The Constitutions of the Holy Apostles Volume II.24, composed c. 380, echoes the Didascalia Apostolorum, alongside a utilization of Luke 7:47.[12] Codex Fuldensis, which was produced in AD 546, and which, in the Gospels, features an unusual system of the text that was found in an earlier certificate, contains the adulterae pericope, in the form in which information technology was written in the Vulgate. More significantly, Codex Fuldensis also preserves the affiliate-headings of its earlier source-document (idea by some researchers to repeat the Diatessaron produced by Tatian in the 170's), and the title of chapter #120 refers specifically to the woman taken in adultery.

The of import codices 50 and Delta do not contain the pericope adulterae, only between John vii:52 and 8:12, each contains a distinct bare space, as a sort of memorial left by the scribe to signify remembrance of the absent passage.

Pacian of Barcelona (bishop from 365 to 391), in the class of making a rhetorical claiming, opposes cruelty equally he sarcastically endorses it: "O Novatians, why do yous delay to ask an eye for an heart? ... Kill the thief. Stone the petulant. Choose not to read in the Gospel that the Lord spared even the adulteress who confessed, when none had condemned her." Pacian was a gimmicky of the scribes who made Codex Sinaiticus.[ commendation needed ]

The writer known equally Ambrosiaster, c. 370/380, mentioned the occasion when Jesus "spared her who had been apprehended in adultery." The unknown author of the limerick "Apologia David" (idea by some analysts to be Ambrose, merely more probably not)[ citation needed ] mentioned that people could be initially taken aback by the passage in which "we see an adulteress presented to Christ and sent away without condemnation." Later in the same limerick he referred to this episode as a "lection" in the Gospels, indicating that it was function of the almanac cycle of readings used in the church-services.

Peter Chrysologus, writing in Ravenna c. 450, clearly cited the pericope adulterae in his Sermon 115. Sedulius and Gelasius too clearly used the passage.[ citation needed ] Prosper of Aquitaine, and Quodvultdeus of Carthage, in the mid-400s, utilized the passage.

A text called the Second Epistle of Pope Callistus section 6[13] contains a quote that may exist from John eight:11 – "Let him come across to it that he sin no more, that the sentence of the Gospel may abide in him: "Go, and sin no more."" However this text also appears to quote from 8th-century writings and therefore is most likely spurious.[xiv]

In Codex Vaticanus, which was produced in the early 300s, perhaps in Egypt (or in Caesarea, by copyists using exemplars from Arab republic of egypt), the text is marked at the finish of John chapter 7 with an "umlaut" in the margin, indicating that an alternative reading was known at this betoken.This codex also has an umlaut aslope blank space following the cease of the Gospel of John, which may convey that whoever added the umlaut was aware of additional text post-obit the end of John 21 – which is where the pericope adulterae is institute in the f-ane group of manuscripts.

Jerome, writing around 417, reports that the pericope adulterae was found in its usual place in "many Greek and Latin manuscripts" in Rome and the Latin Westward. This is confirmed past some Latin Fathers of the 300s and 400s, including Ambrose of Milan, and Augustine. The latter claimed that the passage may take been improperly excluded from some manuscripts in lodge to avoid the impression that Christ had sanctioned adultery:

Sure persons of little religion, or rather enemies of the true religion, fearing, I suppose, lest their wives should be given impunity in sinning, removed from their manuscripts the Lord's act of forgiveness toward the adulteress, as if he who had said, Sin no more, had granted permission to sin.[fifteen]

History of textual criticism on John seven:53–8:11 [edit]

The first to systematically apply the critical marks of the Alexandrian critics was Origen:[sixteen]

In the Septuagint column [Origen] used the system of diacritical marks which was in use with the Alexandrian critics of Homer, specially Aristarchus, marking with an obelus nether unlike forms, as "./.", called lemniscus, and "/.", called a hypolemniscus, those passages of the Septuagint which had null to correspond to in Hebrew, and inserting, chiefly from Theodotion under an asterisk (*), those which were missing in the Septuagint; in both cases a metobelus (Y) marked the end of the notation.

Early textual critics familiar with the utilise and meaning of these marks in classical Greek works like Homer, interpreted the signs to hateful that the department (John 7:53–viii:eleven) was an interpolation and not an original part of the Gospel.

During the 16th century, Western European scholars – both Catholic and Protestant – sought to recover the most right Greek text of the New Testament, rather than relying on the Vulgate Latin translation. At this time, it was noticed that a number of early manuscripts containing John's Gospel lacked John vii:53–8:11 inclusive; and besides that some manuscripts containing the verses marked them with critical signs, ordinarily a lemniscus or asterisk. It was too noted that, in the lectionary of the Greek church, the Gospel-reading for Pentecost runs from John vii:37 to 8:12, but skips over the twelve verses of this pericope.

Beginning with Lachmann (in Federal republic of germany, 1840), reservations well-nigh the pericope became more strongly argued in the modernistic period, and these opinions were carried into the English world by Samuel Davidson (1848–51), Tregelles (1862),[17] and others; the argument against the verses being given body and final expression in Hort (1886). Those opposing the authenticity of the verses as office of John are represented in the 20th century by men similar Cadbury (1917), Colwell (1935), and Metzger (1971).[18]

According to 19th-century text critics Henry Alford and F. H. A. Scrivener the passage was added by John in a second edition of the Gospel forth with v:3.4 and the 21st chapter.[19]

On the other paw, a number of scholars have strongly defended the Johannine authorship of these verses. This grouping of critics is typified by such scholars as Nolan (1865), and Burgon (1886), and Hoskier (1920). More recently it has been defended past David Otis Fuller (1975), and is included in the Greek New Testaments compiled by Wilbur Pickering (1980/2014), Hodges & Farstad (1982/1985), and Robinson & Pierpont (2005). Rather than endorsing Augustine's theory that some men had removed the passage due to a business that it would be used past their wives equally a pretext to commit adultery, Burgon proposed (just did not develop in detail) a theory that the passage had been lost due to a misunderstanding of a feature in the lection-organization of the early church.

Nigh all modern critical translations that include the pericope adulterae practice and then at John 7:53–8:11. Exceptions include the New English Bible and Revised English Bible, which relocate the pericope later the end of the Gospel. Most others enclose the pericope in brackets, or add a footnote mentioning the absenteeism of the passage in the oldest witnesses (e.g., NRSV, NJB, NIV, GNT, NASB, ESV).[2] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26]

[edit]

Arguments against Johannine authorship [edit]

Bishop J.B. Lightfoot wrote that absence of the passage from the earliest manuscripts, combined with the occurrence of stylistic characteristics atypical of John, together implied that the passage was an interpolation. Notwithstanding, he considered the story to be authentic history.[27] Equally a result, based on Eusebius' mention that the writings of Papias contained a story "most a woman falsely accused earlier the Lord of many sins" (H.E. 3.39), he argued that this section originally was function of Papias' Interpretations of the Sayings of the Lord, and included information technology in his collection of Papias' fragments. Bart D. Ehrman concurs in Misquoting Jesus, adding that the passage contains many words and phrases otherwise alien to John'south writing.[28] The evangelical Bible scholar Daniel B. Wallace agrees with Ehrman.[29]

There are several excerpts from Papias that confirm this:

Fragment ane:

And he relates some other story of a adult female, who was accused of many sins earlier the Lord, which is contained in the Gospel co-ordinate to the Hebrews. These things we have thought it necessary to observe in addition to what has been already stated.[30]

Fragment 2:

And in that location was at that time in Menbij [Hierapolis] a distinguished principal who had many treatises, and he wrote five treatises on the Gospel. And he mentions in his treatise on the Gospel of John, that in the book of John the Evangelist, he speaks of a woman who was adulterous, so when they presented her to Christ our Lord, to whom exist celebrity, He told the Jews who brought her to Him, "Whoever of you knows that he is innocent of what she has done, let him testify against her with what he has." So when He told them that, none of them responded with anything and they left.[31]

Fragment 3:

The story of that cheating woman, which other Christians have written in their gospel, was written about by a sure Papias, a student of John, who was declared a heretic and condemned. Eusebius wrote about this. There are laws and that matter which Pilate, the king of the Jews, wrote of. And it is said that he wrote in Hebrew with Latin and Greek above it.[32]

Still, Michael W. Holmes says that it is not certain "that Papias knew the story in precisely this form, inasmuch as it at present appears that at least 2 contained stories nearly Jesus and a sinful woman circulated amongst Christians in the outset two centuries of the church building, so that the traditional class plant in many New Testament manuscripts may well correspond a conflation of two independent shorter, before versions of the incident."[33] Kyle R. Hughes has argued that one of these earlier versions is in fact very similar in style, class, and content to the Lukan special cloth (the so-called "50" source), suggesting that the core of this tradition is in fact rooted in very early Christian (though not Johannine) retentivity.[34]

Arguments for Johannine authorship [edit]

In that location is clear reference to the pericope adulterae in the primitive Christian church in the Syriac Didascalia Apostolorum. (Ii,24,6; ed. Funk I, 93.) Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad contend for Johannine authorship of the pericope.[35] They advise there are points of similarity between the pericope's style and the style of the rest of the gospel. They merits that the details of the encounter fit very well into the context of the surrounding verses. They argue that the pericope'south appearance in the majority of manuscripts, if not in the oldest ones, is show of its authenticity.

Manuscript bear witness [edit]

Both Novum Testamentum Graece (NA28) and the United Bible Societies (UBS4) provide disquisitional text for the pericope, but mark this off with [[double brackets]], indicating that the pericope is regarded equally a subsequently addition to the text.[36]

- Exclude pericope. Papyri 66 (c. 200) and 75 (early third century); Codices Sinaiticus and Vaticanus (4th century), likewise apparently Alexandrinus and Ephraemi (5th), Codices Washingtonianus and Borgianus also from the 5th century, Regius from the 8th (but with a blank space expressing the copyist'south sensation of the passage), Athous Lavrensis (c. 800), Petropolitanus Purpureus, Macedoniensis, Sangallensis (with a distinct blank space) and Koridethi from the 9th century and Monacensis from the tenth; Uncials 0141 and 0211; Minuscules three, 12, 15, xix, 21, 22, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 39, 44, 49, 63, 72, 77, 87, 96, 106, 108, 123, 124, 131, 134, 139, 151, 154, 157, 168, 169, 209, 213, 228, 249, 261, 269, 297, 303, 306, 315, 316, 317, 318, 333, 370, 388, 391, 392, 397, 401, 416, 423, 428, 430, 431, 445, 496, 499, 501, 523, 537, 542, 554, 565, 578, 584, 649, 684, 703, 713, 719, 723, 727, 729, 730, 731, 732, 733, 734, 736, 740, 741, 742, 743, 744, 749, 768, 770, 772, 773, 776, 777, 780, 794, 799, 800, 817, 818, 819, 820, 821, 827, 828, 831, 833, 834, 835, 836, 841, 843, 849, 850, 854, 855, 857, 862, 863, 865, 869, 896, 989, 1077, 1080, 1141 1178, 1230, 1241, 1242, 1253, 1256, 1261, 1262, 1326, 1333, 1357, 1593, 2106, 2193, 2244, 2768, 2862, 2900, 2901, 2907, 2957, 2965 and 2985; the majority of lectionaries; some One-time Latin, the bulk of the Syriac, the Sahidic dialect of the Coptic, the Garima Gospels and other Ethiopic witnesses, the Gothic, some Armenian, Georgian mss. of Adysh (9th century); Diatessaron (second century); plain Cloudless of Alexandria (died 215), other Church Fathers namely Tertullian (died 220), Origen (died 254), Cyprian (died 258), John Chrysostom (died 407), Nonnus (died 431), Cyril of Alexandria (died 444) and Cosmas (died 550).

- Shorter pericope exclude (includes 7:53-8:2 but excludes eight:3-11). 228, 759, 1458, 1663, and 2533.

- Shorter pericope include (8:iii–11). ℓ 4, ℓ 67, ℓ 69, ℓ 70, ℓ 71, ℓ 75, ℓ 81, ℓ 89, ℓ 90, ℓ 98, ℓ 101, ℓ 107, ℓ 125, ℓ 126, ℓ 139, ℓ 146, ℓ 185, ℓ 211, ℓ 217, ℓ 229, ℓ 267, ℓ 280, ℓ 282, ℓ 287, ℓ 376, ℓ 381, ℓ 386, ℓ 390, ℓ 396, ℓ 398, ℓ 402, ℓ 405, ℓ 409, ℓ 417, ℓ 422, ℓ 430, ℓ 431, ℓ 435 (8:2–11), ℓ 462, ℓ 464, ℓ 465, ℓ 520 (eight:2–11).

- Include pericope. Codex Bezae (fifth century), 9th century Codices Boreelianus, Seidelianus I, Seidelianus Two, Cyprius, Campianus, Nanianus, also Tischendorfianus Iv from the tenth, Codex Petropolitanus; Minuscule 28, 318, 700, 892, 1009, 1010, 1071, 1079, 1195, 1216, 1344, 1365, 1546, 1646, 2148, 2174; the Byzantine bulk text; ℓ 79, ℓ 100 (John viii:1–11), ℓ 118, ℓ 130 (viii:1–11), ℓ 221, ℓ 274, ℓ 281, ℓ 411, ℓ 421, ℓ 429 (viii:1–eleven), ℓ 442 (eight:ane–11), ℓ 445 (8:one–11), ℓ 459; the bulk of the Old Latin, the Vulgate (Codex Fuldensis), some Syriac, the Bohairic dialect of the Coptic, some Armenian, Didascalia (tertiary century), Didymus the Blind (4th century), Ambrosiaster (4th century), Ambrose (died 397), Jerome (died 420), Augustine (died 430).

- Question pericope. Marked with asterisks (※), obeli (÷), dash (–) or (<). Codex Vaticanus 354 (S) and the Minuscules 18, 24, 35, 83, 95 (questionable scholion), 109, 125, 141, 148, 156, 161, 164, 165, 166, 167, 178, 179, 200, 201, 202, 285, 338, 348, 363, 367, 376, 386, 392, 407, 478, 479, 510, 532, 547, 553, 645, 655, 656, 661, 662, 685, 699, 757, 758, 763, 769, 781, 789, 797, 801, 824, 825, 829, 844, 845, 867, 897, 922, 1073, 1092 (later hand), 1187, 1189, 1280, 1443, 1445, 2099, and 2253 include entire pericope from 7:53; the menologion of Lectionary 185 includes 8:1ff; Codex Basilensis (E) includes viii:2ff; Codex Tischendorfianus III (Λ) and Petropolitanus (П) also the menologia of Lectionaries ℓ 86, ℓ 211, ℓ 1579 and ℓ 1761 include 8:3ff. Minuscule 807 is a manuscript with a Catena, simply only in John 7:53–8:11 without catena. It is a characteristic of tardily Byzantine manuscripts conforming to the sub-blazon Family One thousandr , that this pericope is marked with obeli; although Maurice Robinson argues that these marks are intended to remind lectors that these verses are to exist omitted from the Gospel lection for Pentecost, not to question the actuality of the passage.

- Shorter pericope questioned (8:3–11) Marked with asterisks (※), obeli (÷) or (<). 4, eight,14, 443, 689, 707, 781, 873, 1517. (8:2-11) Codex Basilensis A. N. III. 12 (E) (8th century),

- Relocate pericope. Family i, minuscules 20, 37, 135, 207, 301, 347, and nearly all Armenian translations place the pericope later on John 21:25; Family 13 identify it after Luke 21:38; a corrector to Minuscule 1333 added 8:3–11 later Luke 24:53; and Minuscule 225 includes the pericope after John vii:36. Minuscule 129, 135, 259, 470, 564, 1076, 1078, and 1356 place John viii:3–11 after John 21:25. 788 and Minuscule 826 placed pericope after Luke 21:38. 115, 552, 1349, and 2620 placed pericope later on John 8:12.

- Added past a later hand. Codex Ebnerianus, 19, 284, 431, 391, 461, 470, 501 (8:iii-11), 578, 794, 1141, 1357, 1593, 2174, 2244, 2860.

The pericope was never read equally a part of the lesson for the Pentecost cycle, but John eight:3–8:eleven was reserved for the festivals of such saints every bit Theodora, 18 September, or Pelagia, 8 Oct.[37]

Some of the textual variants [edit]

- 8:3 – επι αμαρτια γυναικα ] γυναικα επι μοιχεια – D

- 8:4 – εκπειραζοντες αυτον οι ιερεις ινα εχωσιν κατηγοριαν αυτου – D

- viii:five – λιθαζειν ] λιθοβολεισθαι – K Π

- 8:6 – ενος εκαστου αυτων τας αμαρτιας – 264

- eight:6 – μὴ προσποιούμενος – K

- eight:seven – ανακυψας ] αναβλεψας – Κ Γ ] U Λ f 13 700

- viii:8 – κατω κυψας – f 13

- 8:8 – ενος εκαστου αυτων τας αμαρτιας – U, 73, 95, 331, 413, 700

- 8:ix – και υπο της συνειδησεως αλεγχομενοι εξρχοντο εις καθ' εις – K

- 8:nine – εως των εσχατων – U Λ f 13

- 8:10 – και μηδενα θασαμενος πλην της γυναικος – K

- 8:11 – τουτο δε ειπαν πειραζοντες αυτον ινα εχωσιν κατηγοριαν κατ αυτου – One thousand

In culture [edit]

The story is the subject of several paintings, including:

- Christ and the Woman Taken in Infidelity by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1565)

- The Woman Taken in Adultery by Rembrandt (1644)

- Christ and the Woman Taken in Infidelity by Peter Paul Rubens (1899)

- Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery past Max Beckmann (1917)

- Christ with the Adulteress by Han van Meegeren (1942), but sold as an original Vermeer

Variations of the story are told in the 1986 science fiction novel Speaker for the Dead past Orson Scott Card, as office of Letters to an Incipient Heretic by the character San Angelo.[38] [39]

In September 2020, the Chinese textbook 《职业道德与法律》 (transl. Professional Ethics and Law ) was alleged to inaccurately recount the story with a changed narrative in which Jesus stones the adult female, while claiming to be a sinner:[40] [41]

Once upon a fourth dimension, Jesus spoke to an angry oversupply that wanted to kill a guilty woman. "Of all of you, he who can say he has never done annihilation wrong tin can come forrad and kill her." Later they heard this, the oversupply stopped. When the oversupply retreated, Jesus raised a stone and killed the woman, and said, "I am also a sinner, simply if the law can only be executed by a spotless person, then the police force will die."

The publisher claims that this was an inauthentic, unauthorized publication of its textbook.[42]

See also [edit]

- List of New Testament verses not included in modern English translations

- Parable of the Two Debtors

Other questioned passages [edit]

- Comma Johanneum

- The Longer Ending of Mark

- Matthew xvi:2b–3

- Christ'due south agony at Gethsemane

- John five:3b-4

- Doxology to the Lord's Prayer

- Luke 22:19b-20

Sortable manufactures [edit]

- List of omitted Bible verses

- John 21

- Textual criticism

Notes [edit]

- ^ Pronunciation: pə-RIK-ə-pee ə-DUL-tər-ee, Ecclesiastical Latin: [peˈrikope aˈdultere].

References [edit]

- ^ Deuteronomy 22:24

- ^ a b Wallace, Daniel B. (2009). Copan, Paul; Craig, William Lane (eds.). Contending with Christianity's Critics: Answering New Atheists and Other Objectors. B&H Publishing Grouping. pp. 154–155. ISBN978-one-4336-6845-6.

- ^ "Sed hoc videlicet infidelium sensus exhorret, ita ut nonnulli modicae fidei vel potius inimici verae fidei, credo, metuentes peccandi impunitatem dari mulieribus suis, illud, quod de adulterae indulgentia Dominus fecit, auferrent de codicibus suis, quasi permissionem peccandi tribuerit qui dixit: Iam deinceps noli peccare, aut ideo not debuerit mulier a md Deo illius peccati remissione sanari, ne offenderentur insani." – Augustine, De Adulterinis Conjugiis ii:6–7. Cited in Wieland Willker, A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels Archived nine April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 4b, p. 10.

- ^ 'Pericope adulterae', in FL Cross (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, (New York: Oxford University Printing, 2005).

- ^ Jerusalem Bible, reference at John 7:53

- ^ This phrase terra terram accusat is besides given in the Gospel Book of Hitda of Maschede and a ninth-century glossa, Codex Sangelensis 292, and a sermon past Jacobus de Voragine attributes the utilise of these words to Ambrose and Augustine, and other phrases to the Glossa Ordinaria and John Chrysostom, who is commonly considered as not referencing the Pericope. — see Knust, Jennifer; Wasserman, Tommy, "Globe accuses world: tracing what Jesus wrote on the ground" Archived 6 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Harvard Theological Review, 1 October 2010

- ^ E.g., Britni Danielle, "Cast the First Stone: Why Are We So Judgmental?", Clutch, 21 February 2011

- ^ E.g., Mudiga Affe, Gbenga Adeniji, and Etim Ekpimah, "Go and sin no more than, priest tells Bode George Archived 2011-03-02 at the Wayback Motorcar", The Punch, 27 Feb 2011.

- ^ Phrase Finder is copyright Gary Martin, 1996–2015. All rights reserved. "To cast the offset stone". phrases.org.u.k..

- ^ An uncommon usage, evidently not found in the Lxx, but supported in Liddell & Scott'south Greek-English Lexicon (8th ed., NY, 1897) s.v. γραμμα, page 317 col. 2, citing (among others) Herodotus (repeatedly) including 2:73 ("I have not seen one except in an illustration") & 4:36 ("cartoon a map"). See also, Chris Keith, The Pericope Adulterae, the Gospel of John, and the Literacy of Jesus (2009, Leiden, Neth., Brill) page nineteen.

- ^ Expositor's Greek Testament on John 8, accessed 9 May 2016

- ^ The Early Church Fathers Volume 7 past Philip Schaff (public domain) pp. 388–390, 408

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament", Cornerstone Publications (2008), p. 571, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ The Early church building Fathers Volume eight: The Twelve Patriarchs, Excerpts and Epistles, The Clementia, Apocrypha, Decretals, Memoirs of Edessa and Syriac Documents, Remains of the First past Philip Schaff (public domain) pp. 607, 618

- ^ "Sed hoc videlicet infidelium sensus exhorret, ita ut nonnulli modicae fidei vel potius inimici verae fidei, credo, metuentes peccandi impunitatem dari mulieribus suis, illud, quod de adulterae indulgentia Dominus fecit, auferrent de codicibus suis, quasi permissionem peccandi tribuerit qui dixit: Iam deinceps noli peccare, aut ideo not debuerit mulier a medico Deo illius peccati remissione sanari, ne offenderentur insani." Augustine, De Adulterinis Conjugiis ii:6–7. Cited in Wieland Willker, A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels Archived 2011-04-09 at the Wayback Auto, Vol. 4b, p. 10.

- ^ "New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Cognition, Vol. Ii: Basilica – Chambers". ccel.org.

- ^ S. P. Tregelles, An Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scripture (London 1856), pp. 465–468.

- ^ Bruce Thou. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 187–189.

- ^ F. H. A. Scrivener (1883). "A Evidently Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (tertiary edition, 1883, London)". George Bell & Sons. p. 610.

- ^ NIV: "[The primeval manuscripts and many other ancient witnesses exercise not have John 7:53—eight:11. A few manuscripts include these verses, wholly or in role, after John vii:36, John 21:25, Luke 21:38 or Luke 24:53.]" https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John%207%3A53-8%3A11&version=NIV

- ^ NRSV: "John eight:11 The most ancient authorities lack 7.53—8.xi; other authorities add the passage here or afterward 7.36 or after 21.25 or after Luke 21.38, with variations of text; some mark the passage every bit doubtful." https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John%207%3A53-8%3A11&version=NRSV

- ^ NABRE: "7:53–8:11 The story of the woman caught in adultery is a later insertion here, missing from all early Greek manuscripts. A Western text-type insertion, attested mainly in Old Latin translations, it is establish in different places in different manuscripts: here, or subsequently Jn seven:36 or at the end of this gospel, or after Lk 21:38, or at the terminate of that gospel. At that place are many non-Johannine features in the language, and at that place are likewise many doubtful readings within the passage. The manner and motifs are similar to those of Luke, and it fits ameliorate with the full general situation at the end of Lk 21, but it was probably inserted here because of the allusion to Jer 17:thirteen (cf. annotation on Jn viii:six) and the statement, "I practise non gauge anyone," in Jn eight:xv. The Catholic Church accepts this passage as canonical scripture." https://world wide web.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+7%3A53-8%3A11&version=NABRE

- ^ NCB: "John 7:53 This story is missing in a number of ancient manuscripts and is inserted at other points in others; it does not seem to be from the author of the fourth Gospel, for information technology is written in quite a dissimilar style. However, information technology has been accepted past the Church equally the piece of work of an inspired author. We are struck by the portrait of Jesus institute herein: his silence, his sober gesture, his refusal to use religion every bit a pretext to spy on and judge others, and his courage to proclaim his own truth. It is pointless to ask what he wrote on the footing. Let us dwell on what he considered the Constabulary to be: it condemns sin not so that people may gauge one another but then that they may experience the need to be saved past God. And information technology is to this salvation that he bears witness." https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+7%3A53-8%3A11&version=NCB

- ^ ESV: "John 7:53 Some manuscripts do non include 7:53–8:11; others add together the passage here or after 7:36 or after 21:25 or after Luke 21:38, with variations in the text" https://world wide web.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+seven%3A53-viii%3A11&version=ESV

- ^ NASB: "John vii:53 Afterwards mss add the story of the cheating woman, numbering it as John seven:53-viii:11" https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+seven%3A53-8%3A11&version=NASB

- ^ NIV, NRSV, NABRE, NCB, NASB, and ESV put the whole passage between unmarried or double foursquare brackets equally a marker of inauthenticity.

- ^ "The passages which touch Christian sentiment, or history, or morals, and which are affected by textual differences, though less rare than the former, are nevertheless very few. Of these, the pericope of the woman taken in adultery holds the first place of importance. In this example a deference to the most aboriginal authorities, besides as a consideration of internal evidence, might seem to involve immediate loss. The all-time solution may be to place the passage in brackets, for the purpose of showing, not, indeed, that it contains an untrue narrative (for, whencesoever information technology comes, it seems to bear on its face the highest credentials of accurate history), but that prove external and internal is against its beingness regarded as an integral portion of the original Gospel of St. John." J.B. Lightfoot, R.C. Trench, C.J. Ellicott, The Revision of the English language Version of the NT, intro. P. Schaff, (Harper & Bro. NY, 1873) Online at CCEL (Christian Classic Ethereal Library)

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2008). Whose Word is It?: The Story Behind who Inverse the New Testament and why. Continuum. p. 65. ISBN978-i-84706-314-4.

- ^ Phillips, Peter (2016). Hunt, Steven A.; Tolmie, D. Francois; Zimmermann, Ruben (eds.). Graphic symbol Studies in the 4th Gospel. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 408. ISBN978-0-8028-7392-vii.

- ^ -Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History three.39.sixteen

- ^ -Agapius of Menbij, Universal History, Year 12 of Trajan [110AD]

- ^ Vardan Arewelts'i, Explanations of Holy Scripture (translation by Robert Bedrosian)

- ^ Michael W. Holmes in The Apostolic Fathers in English (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), p. 304

- ^ Kyle R. Hughes, "The Lukan Special Fabric and the Tradition History of the Pericope Adulterae," Novum Testamentum 55.3 (2013): 232–251

- ^ "If information technology is not an original office of the Fourth Gospel, its author would have to be viewed as a skilled Johannine imitator, and its placement in this context every bit the shrewdest piece of interpolation in literary history!" The Greek New Attestation Co-ordinate to the Majority Text with Apparatus: Second Edition, by Zane C. Hodges (Editor), Arthur L. Farstad (Editor) Publisher: Thomas Nelson; ISBN 0-8407-4963-5

- ^ Describing its apply of double brackets UBS4 states that they "enclose passages that are regarded as later additions to the text, but are of evident artifact and importance."

- ^ F. H. A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Attestation (1894), vol. II, p. 367.

- ^ Bill of fare, Orson Scott (1992). Speaker for the Dead. Ender Quintet Series. Tom Doherty Associates. p. 204. ISBN978-0-312-85325-ix.

- ^ Walton, John H. (2012). Task. The NIV Application Commentary. Zondervan Academic. p. 372. ISBN978-0-310-49200-nine.

- ^ "Chinese Catholics aroused over book claiming Jesus killed sinner - UCA News". ucanews.com. 22 September 2020. Retrieved 21 Dec 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "[Readings] The New New Attestation, Translated by Annie Geng". Harper's Magazine. December 2020. thirteen November 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "关于《职业道德与法律》的相关声明". world wide web.uestcp.com.cn. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

9月20日我社收到省民宗委消息,一本自称电子科技大学出版社出版的教材《职业道德与法律》,其中的宗教内容误导读者,伤害基督信众感情,造成了恶劣影响。得知情况后,我社高度重视,立即组织人员进行认真核查。经核查,我社正式出版的《职业道德与法律》(ISBN 978-vii-5647-5606-2,主编:潘中梅,李刚,胥宝宇)一书,与该"教材"的封面不同、体例不同,书中也没有涉及上述宗教内容。经我社鉴定,该"教材"是一本盗用我社社名、书号的非法出版物。为维护广大读者的利益和我社的合法权益,我社已向当地公安机关报案,并向当地"扫黄打非"办公室进行举报。凡未经我社授权擅自印制、发行或无法说明图书正当来源的行为,我社将依法追究相关机构和个人的法律责任。对提供侵权行为线索的人员,一经查实,我社将予以奖励。

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links [edit]

- John 7:53–8:eleven (NIV)

- John vii:53-8:eleven (KJV)

- Pericope Adulterae in Manuscript Comparator — allows two or more than New Testament manuscript editions' readings of the passage to be compared in side by side and unified views (similar to diff output)

- The Pericope de Adultera Homepage Site dedicated to proving that the passage is authentic, with links to a broad range of scholarly published material on both sides virtually all aspects of this text, and dozens of new articles.

- New Attestation Virtual Manuscript Room, the manuscript portal provided by the Institute for New Testament Textual Research. This page provides straight access to the primary source material to confirm the bear witness presented in the section Manuscript Show.

- Jesus and the Adulteress, a detailed study by Wieland Willker.

- Apropos the Story of the Adulteress in the Eighth Chapter of John, list marginal notes from several versions, extended discussion taken from Samuel P. Tregelles, lists extended excerpts from An Account of the Printed Text of the Greek New Testament (London, 1854), F.H.A. Scrivener, A Apparently Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament (4th edition. London, 1894), Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Attestation (Stuttgart, 1971), Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (i–xii), in the Anchor Bible series (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1966).

- The Woman Taken In Adultery (John 7:53–8:11), in defense of the pericope de adultera past Edward F. Hills, taken from chapter 6 of his book, The Male monarch James Version Dedicated, quaternary edition (Des Moines: Christian Research Press, 1984).

- Chris Keith, The Initial Location of the Pericope Adulterae in Fourfold Tradition

- David Robert Palmer, John 5:3b and the Pericope Adulterae

- John David Punch, THE PERICOPE ADULTERAE: THEORIES OF INSERTION & OMISSION

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus_and_the_woman_taken_in_adultery

0 Response to "Jesus Said That He Laid Down His Life Is That He Would Pick It Up Again King James Bible Gateway"

Post a Comment